2 Vectors, matrices, and tensors in machine learning

This chapter covers

- Vectors and matrices and their role in datascience

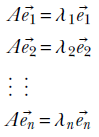

- Working with eigenvalues and eigenvectors

- Finding the axes of a hyper-ellipse

At its core, machine learning, and indeed all computer software, is about number crunching. We input a set of numbers into the machine and get back a different set of numbers as output. However, this cannot be done randomly. It is important to organize these numbers appropriately and group them into meaningful objects that go into and come out of the machine. This is where vectors and matrices come in. These are concepts that mathematicians have been using for centuries—we are simply reusing them in machine learning.

In this chapter, we will study vectors and matrices, primarily from a machine learning point of view. Starting from the basics, we will quickly graduate to advanced concepts, restricting ourselves to topics relevant to machine learning.

We provide Jupyter Notebook-based Python implementations for most of the concepts discussed in this and other chapters. Complete, fully functional code that can be downloaded and executed (after installing Python and Jupyter Notebook) can be found at http://mng.bz/KMQ4. The code relevant to this chapter can be found at http://mng.bz/d4nz.

2.1 Vectors and their role in machine learning

Let’s revisit the machine learning model for a cat brain introduced in section 1.3. It takes two numbers as input, representing the hardness and sharpness of the object in front of the cat. The cat brain processes the input and generates an output threat score that leads to a decision to run away or ignore or approach and purr. The two input numbers usually appear together, and it will be handy to group them into a single object. This object will be an ordered sequence of two numbers, the first representing hardness and the second representing sharpness. Such an object is a perfect example of a vector.

Thus, a vector can be thought of as an ordered sequence of two or more numbers, also known as an array of numbers.1 Vectors constitute a compact way of denoting a set of numbers that together represent some entity. In this book, vectors are represented by lowercase letters with an overhead arrow and arrays by square brackets. For instance, the input to the cat brain model in section 1.3 was a vector  , where x0 represented hardness and x1 represented sharpness.

, where x0 represented hardness and x1 represented sharpness.

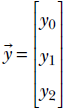

Outputs to machine learning models are also often represented as vectors. For instance, consider an object recognition model that takes an image as input and emits a set of numbers indicating the probabilities that the image contains a dog, human, or cat, respectively. The output of such a model is a three element vector  , where the number y0 denotes the probability that the image contains a dog, y1 denotes the probability that the image contains a human, and y2 denotes the probability that the image contains a cat. Figure 2.1 shows some possible input images and corresponding output vectors.

, where the number y0 denotes the probability that the image contains a dog, y1 denotes the probability that the image contains a human, and y2 denotes the probability that the image contains a cat. Figure 2.1 shows some possible input images and corresponding output vectors.

Figure 2.1 Input images and corresponding output vectors denoting probabilities that the image contains a dog and/or human and/or cat, respectively. Example output vectors are shown.

In multilayered machines like neural networks, the input and output to a layer can be vectors. We also typically represent the parameters of the model function (see section 1.3) as vectors. This is illustrated in section 2.3.

Table 2.1 Toy documents and corresponding feature vectors describing them. Words eligible for the feature vector are bold. The first element of the feature vector indicates the number of occurrences of the word gun and the second violence.

|

Docid |

Document |

Feature vector |

|---|---|---|

|

d0 |

Roses are lovely. Nobody hates roses. |

[0 0] |

|

d1 |

Gun violence has reached an epidemic proportion in America. |

[1 1] |

|

d2 |

The issue of gun violence is really over-hyped. One can find many instances of violence, where no guns were involved. |

[2 2] |

|

d3 |

Guns are for violence prone people. Violence begets guns. Guns beget violence. |

[3 3] |

|

d4 |

I like guns but I hate violence. I have never been involved in violence. But I own many guns. Gun violence is incomprehensible to me. I do believe gun owners are the most anti violence people on the planet. He who never uses a gun will be prone to senseless violence. |

[5 5] |

|

d5 |

Guns were used in a armed robbery in San Francisco last night. |

[1 0] |

|

d6 |

Acts of violence usually involves a weapon. |

[0 1] |

One particularly significant notion in machine learning and data science is the idea of a feature vector. This is essentially a vector that describes various properties of the object being dealt with in a particular machine learning problem. We will illustrate the idea with an example from the world of natural language processing (NLP). Suppose we have a set of documents. We want to create a document retrieval system where, given a new document, we have to retrieve similar documents in the system. This essentially boils down to estimating the similarity between documents in a quantitative fashion. We will study this problem in detail later, but for now, we want to note that the most natural way to approach this is to create feature vectors for each document that quantitatively describe the document. In section 2.5.6, we will see how to measure the similarity between these vectors; here, let’s focus on simply creating descriptor vectors for the documents. A popular way to do this is to choose a set of interesting words (we typically exclude words like “and,” “if,” and “to” that are present in all documents from this list), count the number of occurrences of those interesting words in each document, and make a vector of those values. Table 2.1 shows a toy example with six documents and corresponding feature vectors. For simplicity, we have considered only two of the possible set of words: gun and violence, plural or singular, uppercase or lowercase.

As a different example, the sequence of pixels in an image can also be viewed as a feature vector. Neural networks in computer vision tasks usually expect this feature vector.

2.1.1 The geometric view of vectors and its significance in machine learning

Vectors can also be viewed geometrically. The simplest example is a two-element vector ![]() . Its two elements can be taken to be x and y, Cartesian coordinates in a two-dimensional space, in which case the vector corresponds to a point in that space. Vectors with n elements represent points in an n-dimensional space. The ability to see inputs and outputs of a machine learning model as points allows us to view the model itself as a geometric transformation that maps input points to output points in some high-dimensional space. We have already seen this in section 1.4. It is an enormously powerful concept we will use throughout the book.

. Its two elements can be taken to be x and y, Cartesian coordinates in a two-dimensional space, in which case the vector corresponds to a point in that space. Vectors with n elements represent points in an n-dimensional space. The ability to see inputs and outputs of a machine learning model as points allows us to view the model itself as a geometric transformation that maps input points to output points in some high-dimensional space. We have already seen this in section 1.4. It is an enormously powerful concept we will use throughout the book.

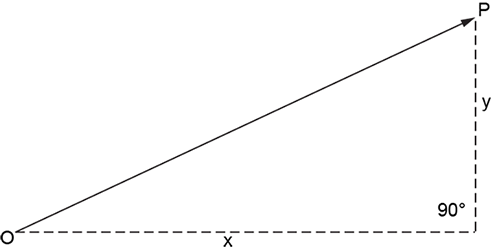

A vector represents a point in space. Also, an array of coordinate values like ![]() describes the position of one point in a given coordinate system. Hence, an array (of coordinate values) can be viewed as the quantitative representation of a vector. See figure 2.2 to get an intuitive understanding of this.

describes the position of one point in a given coordinate system. Hence, an array (of coordinate values) can be viewed as the quantitative representation of a vector. See figure 2.2 to get an intuitive understanding of this.

Figure 2.2 A vector describing the position of point P with respect to point O. The basic mental picture is an arrowed line. This agrees with the definition of a vector that you may have learned in high school: a vector has a magnitude (length of the arrowed line) and direction (indicated by the arrow). On a plane, this is equivalent to the ordered pair of numbers x, y, where the geometric interpretations of x and y are as shown in the figure. In this context, it is worthwhile to note that only the relative positions of the points O and P matter. If both the points are moved, keeping their relationship intact, the vector does not change.

For a real life example, consider the plane of a page of this book. Suppose we want to reach the top-right corner point of the page from the bottom-left corner. Let’s call the bottom-left corner O and the top-right corner P. We can travel the width (8.5 inches) to the right to reach the bottom-left corner and then travel the height (11 inches) upward to reach the top-right corner. Thus, if we choose a coordinate system with the bottom-left corner as the origin and the X-axis along the width, and the Y-axis along the height, point P corresponds to the array representation ![]() . But we could also travel along the diagonal from the bottom-left to the top-right corner to reach P from O. Either way, we end up at the same point P.

. But we could also travel along the diagonal from the bottom-left to the top-right corner to reach P from O. Either way, we end up at the same point P.

This leads to a conundrum. The vector ![]() represents the abstract geometric notion “position of P with respect to O” independent of our choice of coordinate axes. On the other hand, the array representation depends on the choice of a coordinate system. For example, the array

represents the abstract geometric notion “position of P with respect to O” independent of our choice of coordinate axes. On the other hand, the array representation depends on the choice of a coordinate system. For example, the array ![]() represents the top-right corner point P only under a specific choice of coordinate axes (parallel to the sides of the page) and a reference point (bottom-left corner). Ideally, to be unambiguous, we should specify the coordinate system along with the array representation. Why don’t we ever do this in machine learning? Because in machine learning, it doesn’t exactly matter what the coordinate system is as long as we stick to any fixed coordinate system. Machine learning is about minimizing loss functions (which we will study later). As such, absolute positions of point are immaterial, only relative positions matter.

represents the top-right corner point P only under a specific choice of coordinate axes (parallel to the sides of the page) and a reference point (bottom-left corner). Ideally, to be unambiguous, we should specify the coordinate system along with the array representation. Why don’t we ever do this in machine learning? Because in machine learning, it doesn’t exactly matter what the coordinate system is as long as we stick to any fixed coordinate system. Machine learning is about minimizing loss functions (which we will study later). As such, absolute positions of point are immaterial, only relative positions matter.

There are explicit rules (which we will study later) that state how the vector transforms when the coordinate system changes. We will invoke them when necessary. All vectors used in a machine learning computation must consistently use the same coordinate system or be transformed appropriately.

One other point: planar spaces, such as the plane of the paper on which this book is written, are two-dimensional (2D). The mechanical world we live in is three-dimensional (3D). Human imagination usually fails to see higher dimensions. In machine learning and data science, we often talk of spaces with thousands of dimensions. You may not be able to see those spaces in your mind, but that is not a crippling limitation. You can use 3D analogues in your head. They work in a surprisingly large variety of cases. However, it is important to bear in mind that this is not always true. Some examples where the lower-dimensional intuitions fail at higher dimensions will be shown later.

2.2 PyTorch code for vector manipulations

PyTorch is an open source machine learning library developed by Facebook’s artificial intelligence group. It is one of the most elegant practical tools for developing deep learning applications at present. In this book, we aim to familiarize you with PyTorch and similar programming paradigms alongside the relevant mathematics. Knowledge of Python basics will be assumed. You are strongly encouraged to try out all the code snippets in this book (after installing the appropriate packages like PyTorch, that is).

All the Python code in this book is produced via Jupyter Notebook. A summary of the theoretical material presented in the code is provided before the code snippet.

2.2.1 PyTorch code for the introduction to vectors

Listing 2.1 shows how to create and access vectors and subvectors and slice and dice vectors using PyTorch.

NOTE Fully functional code demonstrating how to create a vector and access its elements, executable via Jupyter Notebook, can be found at http://mng.bz/xm8q.

Listing 2.1 Introduction to vectors via PyTorch

v = torch.tensor([0.11, 0.01, 0.98, 0.12, 0.98, ① ,0.85, 0.03, 0.55, 0.49, 0.99, 0.02, 0.31, 0.55, 0.87, 0.63], dtype=torch.float64) ② first_element = v[0] third_element = v[2] ③ last_element = v[-1] second_last_element = v[-2] ④ second_to_fifth_elements = v[1:4] ⑤ first_to_third_elements = v[:2] last_two_elements = v[-2:] ⑥ num_elements_in_v = len(v) u = np.array([0.11, 0.01, 0.98, 0.12, 0.98, 0.85, 0.03, 0.55, 0.49, 0.99, 0.02, 0.31, 0.55, 0.87, 0.63]) u = torch.from_numpy(u) ⑦ diff = v.sub(u) ⑧ u1 = u.numpy() ⑨

① torch.tensor represents a multidimensional array. The vector is a 1D tensor that can be initialized by directly specifying values.

② Tensor elements are floats by default. We can force tensors to be other types such as float64 (double).

③ The square bracket operator lets us access individual vector elements.

④ Negative indices count from the end of the array. –1 denotes the last element. -2 denotes the second-to-last element.

⑤ The colon operator slices off a range of elements from the vector.

⑥ Nothing before a colon denotes the beginning of~the~array. Nothing after a colon denotes the end~of~the array.

⑦ Torch tensors can be initialized from NumPy arrays.

⑧ The difference between the Torch tensor and its NumPy version is zero.

⑨ Torch tensors can be converted to NumPy arrays.

2.3 Matrices and their role in machine learning

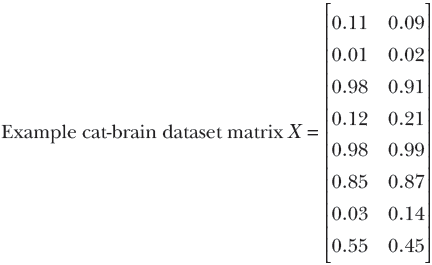

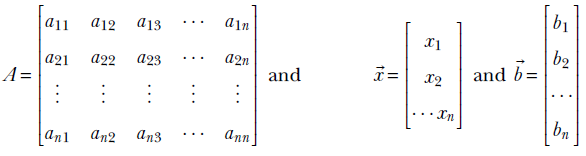

Sometimes it is not sufficient to group a set of numbers into a vector. We have to collect several vectors into another group. For instance, consider the input to training a machine learning model. Here we have several input instances, each consisting of a sequence of numbers. As seen in section 2.1, the sequence of numbers belonging to a single input instance can be grouped into a vector. How do we represent the entire collection of input instances? This is where the concept of matrices comes in handy from the world of mathematics. A matrix can be viewed as a rectangular array of numbers arranged in a fixed count of rows and columns. Each row of a matrix is a vector, and so is each column. Thus a matrix can be thought of as a collection of row vectors. It can also be viewed as a collection of column vectors. We can represent the entire set of numbers that constitute the training input to a machine learning model as a matrix, with each row vector corresponding to a single training instance.

Consider our familiar cat-brain problem again. As stated earlier, a single input instance to the machine is a vector ![]() , where x0 describes the hardness of the object in front of the cat. Now consider a training dataset with many such input instances, each with a known output threat score. You might recall from section 1.1 that the goal in machine learning is to create a function that maps these inputs to their respective outputs with as little overall error as possible. Our training data may look as shown in table 2.2 (note that in real-life problems, the training dataset is usually large—often millions of input-output pairs—but in this toy problem, we will have 8 training data instances).

, where x0 describes the hardness of the object in front of the cat. Now consider a training dataset with many such input instances, each with a known output threat score. You might recall from section 1.1 that the goal in machine learning is to create a function that maps these inputs to their respective outputs with as little overall error as possible. Our training data may look as shown in table 2.2 (note that in real-life problems, the training dataset is usually large—often millions of input-output pairs—but in this toy problem, we will have 8 training data instances).

Table 2.2 Example training dataset for our toy machine learning–based cat brain

|

Input value: Hardness |

Input value: Sharpness |

Output: Threat score |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

0 |

0.11 |

0.09 |

−0.8 |

|

1 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

−0.97 |

|

2 |

0.98 |

0.91 |

0.89 |

|

3 |

0.12 |

0.21 |

−0.68 |

|

4 |

0.98 |

0.99 |

0.95 |

|

5 |

0.85 |

0.87 |

0.74 |

|

6 |

0.03 |

0.14 |

−0.88 |

|

7 |

0.55 |

0.45 |

0.00 |

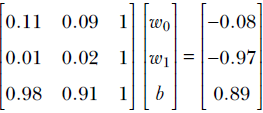

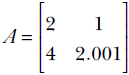

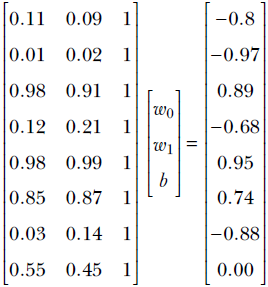

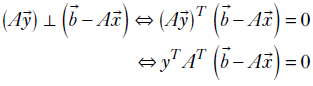

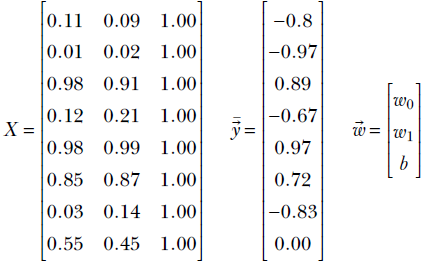

From table 2.2, we can collect the columns corresponding to hardness and sharpness into a matrix, as shown in equation 2.1—this is a compact representation of the training dataset for this problem. 2

Equation 2.1

Each row of matrix X is a particular input instance. Different rows represent different input instances. On the other hand, different columns represent different feature elements. For example, the 0th row of matrix X is the vector [x00 x01] representing the 0th input instance. Its elements, x00 and x01 represent different feature elements, hardness and sharpness respectively of the 0th training input instance.

2.3.1 Matrix representation of digital images

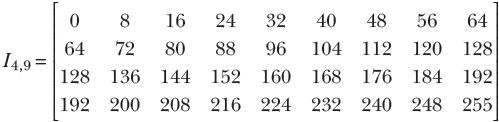

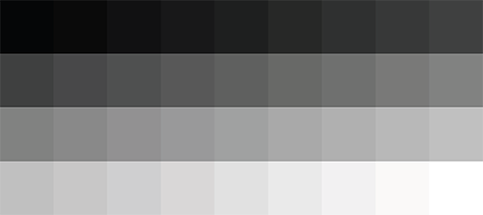

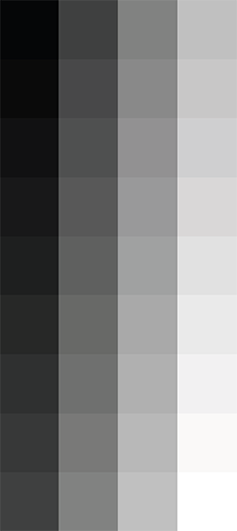

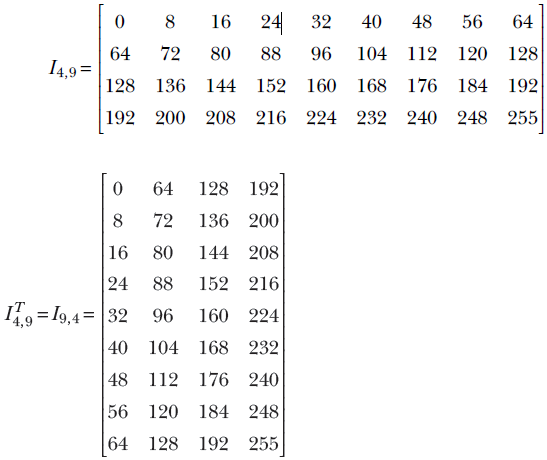

Digital images are also often represented as matrices. Here, each element represents the brightness at a specific pixel position (x, y coordinate) of the image. Typically, the brightness value is normalized to an integer in the range 0 to 255. 0 is black, 255 is white, and 128 is gray.3 Following is an example of a tiny image, 9 pixels wide and 4 pixels high:

Equation 2.2

The brightness increases gradually from left to right and also from top to bottom. I00 represents the top-left pixel, which is black. I3, 8 represents the bottom-right pixel, which is white. The intermediate pixels are various shades of gray between black and white. The actual image is shown in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.3 Image corresponding to matrix I4, 9 in equation 2.2

2.4 Python code: Introducing matrices, tensors, and images via PyTorch

For programming purposes, you can think of tensors as multidimensional arrays. Scalars are zero-dimensional tensors. Vectors are one-dimensional tensors. Matrices are two-dimensional tensors. RGB images are three-dimensional tensors (colorchannels × height × width). A batch of 64 images is a four-dimensional tensor (64 × colorchannels × height × width).

Listing 2.2 Introducing matrices via PyTorch

X = torch.tensor( ① [ [0.11, 0.09], [0.01, 0.02], [0.98, 0.91], [0.12, 0.21], [0.98, 0.99], [0.85, 0.87], [0.03, 0.14], [0.55, 0.45] ② ] ) print("Shape of the matrix is: {}".format(X.shape)) ③ first_element = X[0, 0] ④ row_0 = X[0, :] ⑤ row_1 = X[1, 0:2] ⑥ column_0 = X[:, 0] ⑦ column_1 = X[:, 1] ⑧

① A matrix is a 2D array of numbers: i.e., a 2D tensor. The entire training data input set for a machine-learning model can be viewed as a matrix. Each input instance is one row. Row count ≡ number of training examples, column count ≡ training instance size

② Cat-brain training data input: 8 examples, each with two values (hardness, sharpness). An 8 × 2 tensor is created by specifying values.

③ The shape of a tensor is a list. For a matrix, the first list element is num rows; the second list element is num columns.

④ Square brackets extract individual matrix elements.

⑤ A standalone colon operator denotes all possible indices.

⑥ The colon operator denotes the range of indices.

⑦ 0th column

⑧ 1st column

Listing 2.3 Slicing and dicing matrices

first_3_training_examples = X[:3, ] ① ② print("Sharpness of 5-7 training examples is: {}" .format(X[5:8, 1])) ③

① Ranges of rows and columns can be specified via the colon operator to slice off (extract) submatrices.

② Extracts the first three training examples (rows)

③ Extracts the sharpness feature for the 5th to 7th training examples

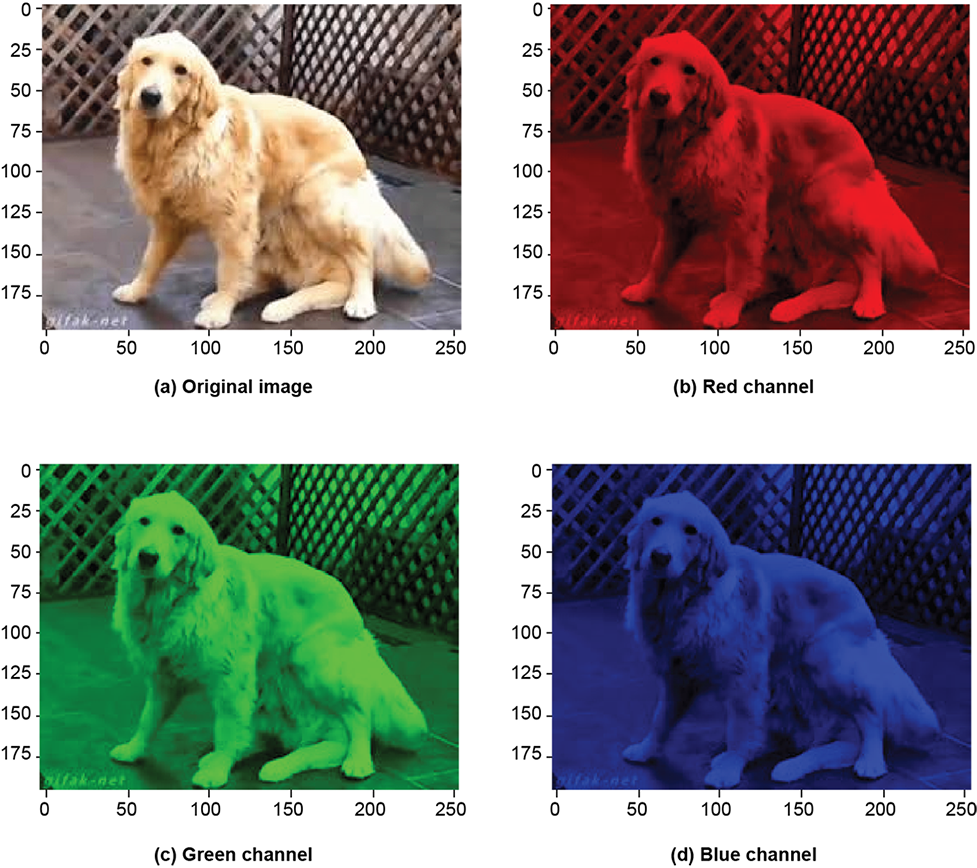

Listing 2.4 Tensors and images in PyTorch

tensor = torch.rand((5, 5, 3)) ① ② I49 = torch.tensor([[0, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64], ③ [64, 72, 80, 88, 96, 104, 112, 120, 128], [128, 136, 144, 152, 160, 168, 176, 184, 192], [192, 200, 208, 216, 224, 232, 240, 248, 255]], ) ④ img = torch.tensor(cv2.imread('../../Figures/dog3.jpg')) ⑤ img_b = img[:, :, 0] ⑥ img_g = img[:, :, 1] ⑥ img_r = img[:, :, 2] ⑥ img_cropped = img[0:100, 0:100, :] ⑦

① PyTorch tensors can be used to represent tensors. A vector is a 1-tensor, a matrix is a 2-tensor, and a scalar is a 0-tensor.

② Creates a random tensor of specified dimensions

③ All images are tensors. An RGB image of height H, width W is a 3-tensor of shape [3, H, W].

④ 4 × 9 single-channel image shown in figure 2.3

⑤ Reads a 199 × 256 × 3 image from disk

⑥ Usual slicing dicing operators work. Extracts the red, green, and blue channels of the image as shown in figure 2.4.

⑦ Crops out a 100 × 100 subimage as shown in figure 2.5

Figure 2.4 Tensors and images in PyTorch

Figure 2.5 Cropped image of dog

2.5 Basic vector and matrix operations in machine learning

In this section, we introduce several basic vector and matrix operations along with examples to demonstrate their significance in image processing, computer vision, and machine learning. It is meant to be an application-centric introduction to linear algebra. But it is not meant to be a comprehensive review of matrix and vector operations, for which you are referred to a textbook on linear algebra.

Figure 2.6 Image corresponding to the transpose of matrix I4, 9 shown in equation 2.3. This is equivalent to rotating the image by 90°.

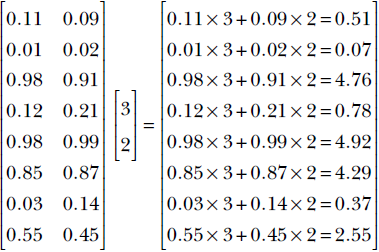

2.5.1 Matrix and vector transpose

In equation 2.2, we encountered the matrix I4, 9 depicting a tiny image. Suppose we want to rotate the image by 90° so it looks like figure 2.5. The original matrix I4, 9 and its transpose I4,T9 = I9, 4 are shown here:

Equation 2.3

By comparing equation 2.2 and equation 2.3, you can easily see that one can be obtained from the other by interchanging the row and column indices. This operation is generally known as matrix transposition.

Formally, the transpose of a matrix Am, n with m rows and n columns is another matrix with n rows and m columns. This transposed matrix, denoted An,Tm, is such that AT[i, j] = A[j, i]. For instance, the value at row 0 column 6 in matrix I4, 9 is 48; in the transposed matrix, the same value appears in row 6 and column 0. In matrix parlance, I4, 9[0,6] = I9,T4[6,0] = 48.

Vector transposition is a special case of matrix transposition (since all vectors are matrices—a column vector with n elements is an n × 1 matrix). For instance, an arbitrary vector and its transpose are shown next:

Equation 2.4

![]()

Equation 2.5

2.5.2 Dot product of two vectors and its role in machine learning

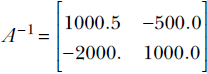

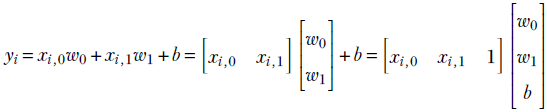

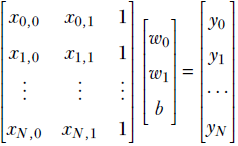

In section 1.3, we saw the simplest of machine learning models where the output is generated by taking a weighted sum of the inputs (and then adding a constant bias value). This model/machine is characterized by the weights w0, w1, and bias b. Take the rows of table 2.2. For example, for row 0, the input values are the hardness of the approaching object = 0.11 and softness = 0.09. The corresponding model output will be y = w0 × 0.11 + w1 × 0.09 + b. In fact, the goal of training is to choose w0, w1, and b such that model outputs are as close as possible to the known outputs; that is, y = w0 × 0.11 + w1 × 0.09 + b should be as close to −0.8 as possible, y = w0 × 0.01 + w1 × 0.02 + b should be as close to −0.97 as possible, that is, in general, given an input instance ![]() , the model output is y = x0w0 + x1w1 + b.

, the model output is y = x0w0 + x1w1 + b.

We will keep returning to this model throughout the chapter. But first, let’s consider a different question. In this toy example, we have only three model parameters: two weights, w0, w1, and one bias b. Hence it is not very messy to write the model output flat out as y = x0w0 + x1w1 + b. But, with longer feature vectors (that is, more weights) it will become unwieldy. Is there a compact way to represent the model output for a specific input instance, irrespective of the size of the input?

Turns out the answer is yes—we can use an operation called dot product from the world of mathematics. We have already seen in section 2.1 that an individual instance of model input can be compactly represented by a vector, say ![]() (it can have any number of input values). We can also represent the set of weights as vector

(it can have any number of input values). We can also represent the set of weights as vector ![]() —it will have the same number of items as the input vector. The dot product is simply the element-wise multiplication of the two vectors

—it will have the same number of items as the input vector. The dot product is simply the element-wise multiplication of the two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() . Formally, given two vectors and

. Formally, given two vectors and  and

and  , the dot product of the two vectors is defined as

, the dot product of the two vectors is defined as

![]()

Equation 2.6

In other words, the sum of the products of corresponding elements of the two vectors is the dot product of the two vectors, denoted ![]() ⋅

⋅ ![]() .

.

NOTE The dot product notation can compactly represent the model output as y = ![]() ⋅

⋅ ![]() + b. The representation does not increase in size even when the number of inputs and weights is large.

+ b. The representation does not increase in size even when the number of inputs and weights is large.

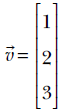

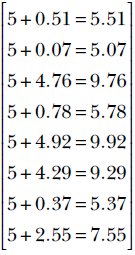

Consider our (by now familiar) cat-brain example again. Suppose the weight vector is  and the bias value b = 5. Then the model output for the 0th input instance from table 2.2 will be

and the bias value b = 5. Then the model output for the 0th input instance from table 2.2 will be  . It is another matter that these are bad choices for weight and bias parameters, since the model output 5.51 is a far cry from the desired output −0.89. We will soon see how to obtain better parameter values. For now, we just need to note that the dot product offers a neat way to represent the simple weighted sum model output.

. It is another matter that these are bad choices for weight and bias parameters, since the model output 5.51 is a far cry from the desired output −0.89. We will soon see how to obtain better parameter values. For now, we just need to note that the dot product offers a neat way to represent the simple weighted sum model output.

NOTE The dot product is defined only if the vectors have the same dimensions.

Sometimes the dot product is also referred to as inner product, denoted ⟨![]() ,

, ![]() ⟩. Strictly speaking, the phrase inner product is a bit more general; it applies to infinite-dimensional vectors as well. In this book, we will often use the terms interchangeably, sacrificing mathematical rigor for enhanced understanding.

⟩. Strictly speaking, the phrase inner product is a bit more general; it applies to infinite-dimensional vectors as well. In this book, we will often use the terms interchangeably, sacrificing mathematical rigor for enhanced understanding.

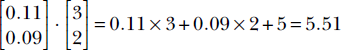

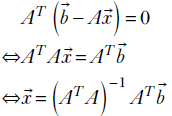

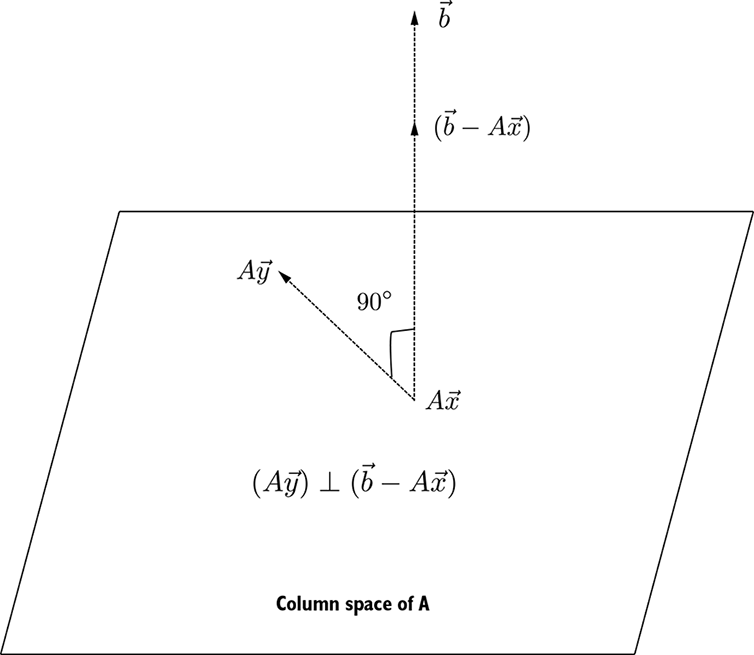

2.5.3 Matrix multiplication and machine learning

Vectors are special cases of matrices. Hence, matrix-vector multiplication is a special case of matrix-matrix multiplication. We will start with that.

Matrix-vector multiplication

In section 2.5.2, we saw that given a weight vector, say ![]() , and the bias value b = 5, the weighted sum model output upon a single input instance, say

, and the bias value b = 5, the weighted sum model output upon a single input instance, say ![]() , can be represented using a vector-vector dot product

, can be represented using a vector-vector dot product ![]() . As depicted in equation 2.1, during training, we are dealing with many training data instances at the same time. In real life, we typically deal with hundreds of thousands of input instances, each having hundreds of values. Is there a way to represent the model output for the entire training dataset compactly, such that it is independent of the count of input instances and their sizes?

. As depicted in equation 2.1, during training, we are dealing with many training data instances at the same time. In real life, we typically deal with hundreds of thousands of input instances, each having hundreds of values. Is there a way to represent the model output for the entire training dataset compactly, such that it is independent of the count of input instances and their sizes?

The answer turns out to be yes. We can use the idea of matrix-vector multiplication from the world of mathematics. The product of a matrix X and column vector ![]() is another vector, denoted X

is another vector, denoted X![]() . Its elements are the dot products between the row vectors of X and the column vector

. Its elements are the dot products between the row vectors of X and the column vector ![]() . For example, given the model weight vector

. For example, given the model weight vector ![]() and the bias value b = 5, the outputs on the toy training dataset of our familiar cat-brain model (equation 2.1) can be obtained via the following steps:

and the bias value b = 5, the outputs on the toy training dataset of our familiar cat-brain model (equation 2.1) can be obtained via the following steps:

Equation 2.7

Adding the bias value of 5, the model output on the toy training dataset is

Equation 2.8

In general, the output of our simple model (biased weighted sum of input elements) can be expressed compactly as ![]() = X

= X![]() +

+ ![]() .

.

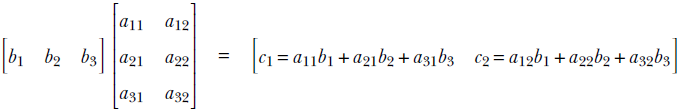

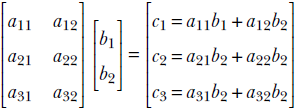

Matrix-matrix multiplication

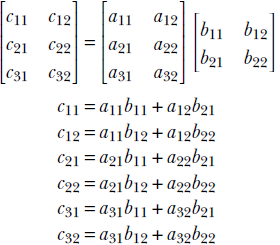

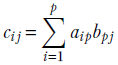

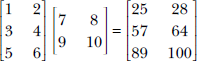

Generalizing the notion of matrix times vector, we can define matrix times matrix. A matrix with m rows and p columns, say Am, p, can be multiplied with another matrix with p rows and n columns, say Bp, n, to generate a matrix with m rows and n columns, say Cm, n: for example, Cm, n = Am, p Bp, n. Note that the number of columns in the left matrix must match the number of rows in the right matrix. Element i, j of the result matrix, Ci, j, is obtained by point-wise multiplication of the elements of the ith row vector of A and the jth column vector of B. The following example illustrates the idea:

The computation for C2, 1 is shown via bolding by way of example.

NOTE Matrix multiplication is not commutative. In general, AB ≠ BA.

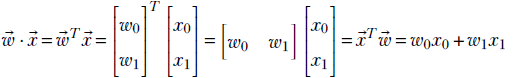

At this point, the astute reader may already have noted that the dot product is a special case of matrix multiplication. For instance, the dot product between two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() is equivalent to transposing either of the two vectors and then doing a matrix multiplication with the other. In other words,

is equivalent to transposing either of the two vectors and then doing a matrix multiplication with the other. In other words,

The idea works in higher dimensions, too. In general, given two vectors  and

and  , the dot product of the two vectors is defined as

, the dot product of the two vectors is defined as

Equation 2.9

Another special case of matrix multiplication is row-vector matrix multiplication. For example, ![]() TA =

TA = ![]() or

or

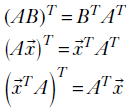

Transpose of matrix products

Given two matrices A and B, where the number of columns in A matches the number of rows in B (that is, it is possible to multiply them), the transpose of the product is the product of the individual transposes, in reversed order. The rule also applies to matrix-vector multiplication. The following equations capture this rule:

Equation 2.10

2.5.4 Length of a vector (L2 norm): Model error

Imagine that a machine learning model is supposed to output a target value ȳ, but it outputs y instead. We are interested in the error made by the model. The error is the difference between the target and the actual outputs.

Let’s apply this idea of squaring to machine learning model error. As seen earlier in section 2.5.3, given a model weight vector, say ![]() , and the bias value b = 5, the weighted sum model output upon a single input instance, say

, and the bias value b = 5, the weighted sum model output upon a single input instance, say ![]() , is

, is ![]() . The corresponding target (ideal) output, from table 2.2, is −0.8. The squared error e2 = (−0.8−5.51)2 = 39.82 gives us an idea of how good or bad the model parameters 3, 2, 5 are. For instance, if we instead use a weight vector

. The corresponding target (ideal) output, from table 2.2, is −0.8. The squared error e2 = (−0.8−5.51)2 = 39.82 gives us an idea of how good or bad the model parameters 3, 2, 5 are. For instance, if we instead use a weight vector ![]() and bias value −1, we get model output

and bias value −1, we get model output ![]() . The output is exactly the same as the target. The corresponding squared error e2 = (−0.8−(−0.8))2 = 0. This (zero error) immediately tells us that 1, 1, −1 are much better choices of model parameters than 3, 2, 5.

. The output is exactly the same as the target. The corresponding squared error e2 = (−0.8−(−0.8))2 = 0. This (zero error) immediately tells us that 1, 1, −1 are much better choices of model parameters than 3, 2, 5.

In general, the error made by a biased weighted sum model can be expressed as follows. If ![]() denotes the weight vector and

denotes the weight vector and ![]() denotes the bias, the output corresponding to an input instance

denotes the bias, the output corresponding to an input instance ![]() can be expressed as y =

can be expressed as y = ![]() ⋅

⋅ ![]() + b. Let ȳ denote the corresponding target (ground truth). Then the error is defined as e = (y−ȳ)2.

+ b. Let ȳ denote the corresponding target (ground truth). Then the error is defined as e = (y−ȳ)2.

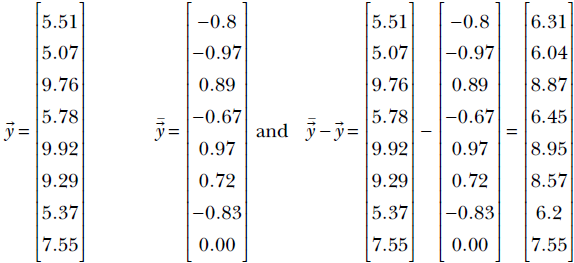

Thus we see that we can compute the error on a single training instance by taking the difference between the model output and the ground truth and squaring it. How do we extend this concept over the entire training dataset? The set of outputs corresponding to the entire set of training inputs can be expressed as the output vector y = X![]() +

+ ![]() . The corresponding target output vector, consisting of the entire set of ground truths can be expressed as

. The corresponding target output vector, consisting of the entire set of ground truths can be expressed as ![]() . The differences between the target and model output over the entire training set can be expressed as another vector

. The differences between the target and model output over the entire training set can be expressed as another vector ![]() -

- ![]() . In our particular example:

. In our particular example:

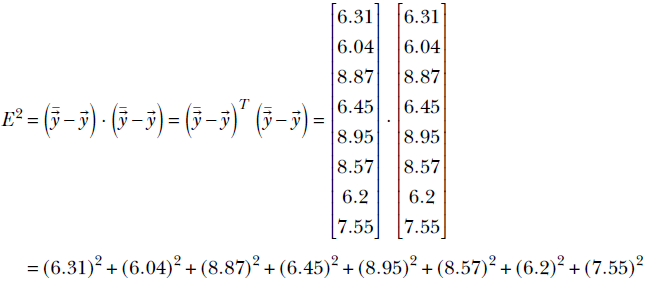

Thus the total error over the entire training dataset is obtained by taking the difference between the output and the ground truth vector, squaring its elements and adding them up. Recalling equation 2.9, this is exactly what will happen if we take the dot product of the difference vector with itself. That happens to be the definition of the squared magnitude or length or L2 norm of a vector: the dot product of the vector with itself. In the previous example, the overall training (squared) error is:

Formally, the length of a vector  , denoted ||

, denoted ||![]() ||, is defined as

||, is defined as ![]() . This quantity is sometimes called the L2 norm of the vector.

. This quantity is sometimes called the L2 norm of the vector.

In particular, given a machine learning model with output vector ![]() and a target vector

and a target vector ![]() , the error is the same as the magnitude or L2 norm of the difference vector

, the error is the same as the magnitude or L2 norm of the difference vector

2.5.5 Geometric intuitions for vector length

For a 2D vector ![]() , as seen in figure 2.2, the L2 norm

, as seen in figure 2.2, the L2 norm ![]() is nothing but the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle whose sides are elements of the vector. The same intuition holds in higher dimensions.

is nothing but the hypotenuse of the right-angled triangle whose sides are elements of the vector. The same intuition holds in higher dimensions.

A unit vector is a vector whose length is 1. Given any vector ![]() , the corresponding unit vector can be obtained by dividing every element by the length of that vector. For example, given

, the corresponding unit vector can be obtained by dividing every element by the length of that vector. For example, given ![]() , length

, length ![]() and the corresponding unit vector

and the corresponding unit vector  . Unit vectors typically represent a direction.

. Unit vectors typically represent a direction.

NOTE Unit vectors are conventionally depicted with the hat symbol as opposed to the little overhead arrow, as in ûTû = 1.

In machine learning, the goal of training is often to minimize the length of the error vector (the difference between the model output vector and the target ground truth vector).

2.5.6 Geometric intuitions for the dot product: Feature similarity

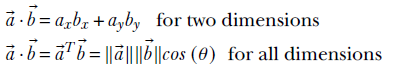

Consider the document retrieval problem depicted in table 2.1 one more time. We have a set of documents, each described by its own feature vector. Given a pair of such documents, we must find their similarity. This essentially boils down to estimating the similarity between two feature vectors. In this section, we will see that the dot product between a pair of vectors can be used as a measure of similarity between them.

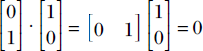

For instance, consider the feature vectors corresponding to d5 and d6 in table 2.1. They are ![]() and

and ![]() . The dot product between them is 1 × 0 + 0 × 1 = 0. This is low and agrees with our intuition that there is no common word of interest between them, so the documents are very dissimilar. On the other hand, the dot product between feature vectors of d3 and d4 is

. The dot product between them is 1 × 0 + 0 × 1 = 0. This is low and agrees with our intuition that there is no common word of interest between them, so the documents are very dissimilar. On the other hand, the dot product between feature vectors of d3 and d4 is ![]() . This is high and agrees with our intuition that they have many commonalities in words of interest and are similar documents. Thus, we get the first glimpse of an important concept. Loosely speaking, similar vectors have larger dot products, and dissimilar vectors have near-zero dot products.

. This is high and agrees with our intuition that they have many commonalities in words of interest and are similar documents. Thus, we get the first glimpse of an important concept. Loosely speaking, similar vectors have larger dot products, and dissimilar vectors have near-zero dot products.

We will keep revisiting this problem of estimating similarity between feature vectors and solve it with more and more finesse. As a first attempt, we will now study in greater detail how dot products measure similarities between vectors. First we will show that the component of a vector along another is yielded by the dot product. Using this, we will show that the “similarity/agreement” between a pair of vectors can be estimated using the dot product between them. In particular, we will see that if the vectors point in more or less the same direction, their dot products are higher than when the vectors are perpendicular to each other. If the vectors point in opposite directions, their dot product is negative.

Dot product measures the component of one vector along another

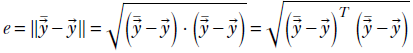

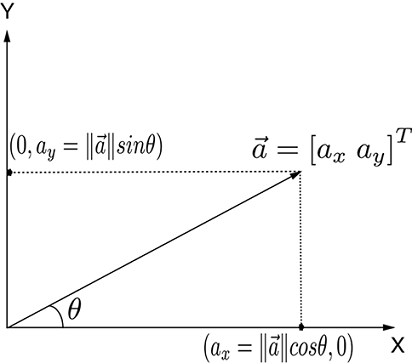

Let’s examine a special case first: the component of a vector along a coordinate axis. This can be obtained by multiplying the length of the vector with the cosine of the angle between the vector and the relevant coordinate axis. As shown for 2D in figure 2.7a, a vector ![]() can be broken into two components along the X and Y axes as

can be broken into two components along the X and Y axes as

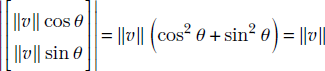

Note how the length of the vector is preserved:

(a) Components of a 2D vector along coordinate axes. Note that ||![]() || is the length of hypotenuse.

|| is the length of hypotenuse.

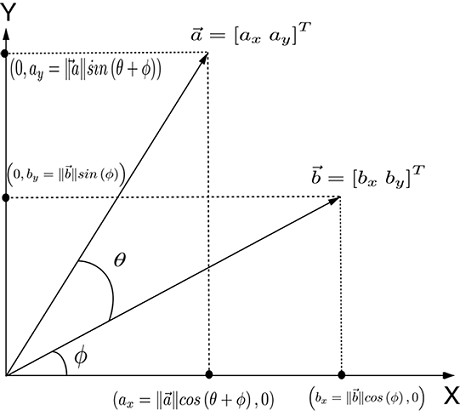

(b) Dot product as a component of one vector along another ![]() ⋅

⋅ ![]() =

= ![]() T

T![]() = axbx + ayby = ||

= axbx + ayby = ||![]() || ||

|| ||![]() ||cos(θ).

||cos(θ).

Figure 2.7 Vector components and dot product

Now let’s study the more general case of the component of one vector in the direction of another arbitrary vector (figure 2.7b). The component of a vector ![]() along another vector

along another vector ![]() is

is ![]() ⋅

⋅ ![]() =

= ![]() T

T![]() . This is equivalent to ||

. This is equivalent to ||![]() || ||

|| ||![]() ||cos(θ), where θ is the angle between the vectors

||cos(θ), where θ is the angle between the vectors ![]() and

and ![]() . (This has been proven for the two-dimension case discussed in section A.1 of the appendix. You can read it if you would like deeper intuition.)

. (This has been proven for the two-dimension case discussed in section A.1 of the appendix. You can read it if you would like deeper intuition.)

Dot product measures the agreement between two vectors

The dot product can be expressed using the cosine of the angle between the vectors. Given two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() , if θ is the angle between them, we have see figure 2.7b)

, if θ is the angle between them, we have see figure 2.7b)

Equation 2.11

Expressing the dot product using cosines makes it easier to see that it measures the agreement (aka correlation) between two vectors. If the vectors have the same direction, the angle between them is 0 and the cosine is 1, implying maximum agreement. The cosine becomes progressively smaller as the angle between the vectors increases, until the two vectors become perpendicular to each other and the cosine is zero, implying no correlation—the vectors are independent of each other. If the angle between them is 180°, the cosine is −1, implying that the vectors are anti-correlated. Thus, the dot product of two vectors is proportional to their directional agreement.

What role do the vector lengths play in all this? The dot product between two vectors is also proportional to the lengths of the vectors. This means agreement scores between bigger vectors are higher (an agreement between the US president and the German chancellor counts more than an agreement between you and me).

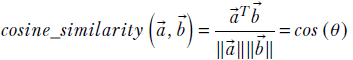

If you want the agreement score to be neutral to the vector length, you can use a normalized dot product between unit-length vectors along the same directions:

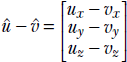

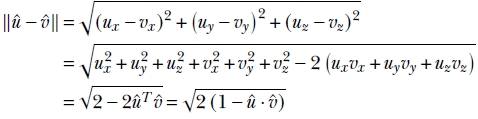

Dot product and the difference between two unit vectors

To obtain further insight into how the dot product indicates agreement or correlation between two directions, consider the two unit vectors  and

and  . The difference between them is

. The difference between them is  .

.

Note that since they are unit vectors, ![]() . The length of the difference vector

. The length of the difference vector

From the last equality, it is evident that a larger dot product implies a smaller difference: that is, more agreement between the vectors.

2.6 Orthogonality of vectors and its physical significance

Try moving an object at right angles to the direction in which you are pushing it. You will find it impossible. The larger the angle, the less effective your force vector becomes (finally becoming totally ineffective at a 90° angle). This is why it is easy to walk on a horizontal surface (you are moving at right angles to the direction of gravitational pull, so the gravity vector is ineffective) but harder on an upward incline (the gravity vector is having some effect against you).

These physical notions are captured mathematically in the notion of a dot product. The dot product between two vectors ![]() (say, the push vector) and

(say, the push vector) and ![]() (say, the displacement of the pushed object vector) is ||

(say, the displacement of the pushed object vector) is ||![]() || ||

|| ||![]() ||cosθ, where θ is the angle between the two vectors. When θ is 0 (the two vectors are aligned), cosθ = 1, the maximum possible value of cosθ, so push is maximally effective. As θ increases, cosθ decreases, and push becomes less and less effective. Finally, at θ = 90°, cosθ = 0, and push becomes completely ineffective.

||cosθ, where θ is the angle between the two vectors. When θ is 0 (the two vectors are aligned), cosθ = 1, the maximum possible value of cosθ, so push is maximally effective. As θ increases, cosθ decreases, and push becomes less and less effective. Finally, at θ = 90°, cosθ = 0, and push becomes completely ineffective.

Two vectors are orthogonal if their dot product is zero. Geometrically, this means the vectors are perpendicular to each other. Physically, this means the two vectors are independent: one cannot influence the other. You can say there is nothing in common between orthogonal vectors. For instance, the feature vector for d5 is ![]() and that for d6 is

and that for d6 is ![]() in table 2.1. These are orthogonal (dot product is zero), and you can easily see that none of the feature words (gun, violence) are common to both documents.

in table 2.1. These are orthogonal (dot product is zero), and you can easily see that none of the feature words (gun, violence) are common to both documents.

2.7 Python code: Basic vector and matrix operations via PyTorch

In this section, we use Python PyTorch code to illustrate many of the concepts discussed earlier.

NOTE Fully functional code for this section, executable via Jupyter Notebook, can be found at http://mng.bz/ryzE.

2.7.1 PyTorch code for a matrix transpose

The following listing shows the PyTorch code for a matrix transpose.

Listing 2.5 Transpose

I49 = torch.stack([torch.arange(0, 72, 8), torch.arange(64, 136, 8), ① torch.arange(128, 200, 8), torch.arange(192, 264, 8)]) I49_t = torch.transpose(I49, 0, 1) ② for i in range(0, I49.shape[0]): for j in range(0, I49.shape[1]): assert I49[i][j] == I49_t[j][i] ③ assert torch.allclose(I49_t, I49.T, 1e-5) ④

① The torch.arange function creates a vector whose elements go from start to stop in increments of step. Here we create a 4 × 9 image corresponding to I4,9 in equation 2.2, shown in figure 2.3.

② The transpose operator interchanges rows and columns. The 4 × 9 image becomes a 9 × 4 image (see figure 2.6. The element at position (i, j) is interchanged with the element at position (j, i).

③ Interchanged elements of the original and transposed matrix are equal.

④ The .T operator retrieves the transpose of an array.

2.7.2 PyTorch code for a dot product

The dot product of two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() represents the components of one vector along the other. Consider two vectors

represents the components of one vector along the other. Consider two vectors ![]() = [a1 a2 a3] and

= [a1 a2 a3] and ![]() = [b1 b2 b3]. Then

= [b1 b2 b3]. Then ![]() .

.![]() = a1b1 + a2b2 + a3b3.

= a1b1 + a2b2 + a3b3.

Listing 2.6 Dot product

a = torch.tensor([1, 2, 3])

b = torch.tensor([4, 5, 6])

a_dot_b = torch.dot(a, b)

print("Dot product of these two vectors is: "

"{}".format(a_dot_b)) ①

# Dot product of perpendicular vectors is zero

vx = torch.tensor([1, 0]) # a vector along X-axis

vy = torch.tensor([0, 1]) # a vector along Y-axis

print("Example dot product of orthogonal vectors:"

" {}".format(torch.dot(vx, vy))) ②

① Outputs 32: 1 ∗ 4 + 2 ∗ 5 + 3 ∗ 6

② Outputs 0: 1 ∗ 0 + 0 ∗ 1

2.7.3 PyTorch code for matrix vector multiplication

Consider a matrix Am, n with m rows and n columns that is multiplied with a vector ![]() n with n elements. The result is a m element column vector

n with n elements. The result is a m element column vector ![]() m . In the following example, m = 3 and n = 2.

m . In the following example, m = 3 and n = 2.

In general,

![]()

Listing 2.7 Matrix vector multiplication

X = torch.tensor([[0.11, 0.09], [0.01, 0.02], [0.98, 0.91], [0.12, 0.21], ① [0.98, 0.99], [0.85, 0.87], [0.03, 0.14], [0.55, 0.45], [0.49, 0.51], [0.99, 0.01], [0.02, 0.89], [0.31, 0.47], [0.55, 0.29], [0.87, 0.76], [0.63, 0.24]]) ② w = torch.rand((2, 1)) ③ b = 5.0 = torch.matmul(X, w) + b ④

① A linear model comprises a weight vector ![]() and bias b. For each training data instance

and bias b. For each training data instance ![]() i, the model outputs yi =

i, the model outputs yi = ![]() iT

iT![]() + b. For the training data matrix X (whose rows are training data instances), the model outputs X

+ b. For the training data matrix X (whose rows are training data instances), the model outputs X![]() +

+ ![]() =

= ![]()

② Cat-brain 15 × 2 training data matrix (equation 2.7)

③ Random initialization of weight vector

④ Model training output: ![]() = X

= X![]() + b. The scalar b is automatically replicated to create a vector.

+ b. The scalar b is automatically replicated to create a vector.

2.7.4 PyTorch code for matrix-matrix multiplication

Consider a matrix Am, p with m rows and p columns. Let’s multiply it with another matrix Bp, n with p rows and n columns. The resultant matrix Cm, n contains m rows and n columns. Note that the number of columns in the left matrix A should match the number of rows in the right matrix B:

In general,

Listing 2.8 Matrix-matrix multiplication

A = torch.tensor([[1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6]]) B = torch.tensor([[7, 8], [9, 10]]) C = torch.matmul(A, B) ① ② w = torch.tensor([1, 2, 3]) x = torch.tensor([4, 5, 6]) assert torch.dot(w, x) == torch.matmul(w.T, x) ③

① C = AB ⟹ C[i, j] is the dot product of the ith row of A and jth column of B.

②

③ The dot product can be viewed as a row matrix multiplied by a column matrix.

2.7.5 PyTorch code for the transpose of a matrix product

Given two matrices A and B, where the number of columns in A matches the number of rows in B, the transpose of their product is the product of the individual transposes in reversed order: (AB)T = BTAT.

Listing 2.9 Transpose of a matrix product

assert torch.all(torch.matmul(A, B).T == torch.matmul(B.T, A.T)) ① assert torch.all(torch.matmul(A.T, x).T == torch.matmul(x.T, A)) ②

① Asserts equality between (AB)T and BTAT

② Applies to matrix-vector multiplication, too: (AT![]() )T =

)T = ![]() TA

TA

2.8 Multidimensional line and plane equations and machine learning

Geometrically speaking, what does a machine learning classifier really do? We provided the outline of an answer in section 1.4. You are invited to review that and especially figures 1.2 and 1.3. We will briefly summarize here.

Inputs to a classifier are feature vectors. These vectors can be viewed as points in some multidimensional feature space. The task of classification then boils down to separating the points belonging to different classes. The points may be all jumbled up in the input space. It is the model’s job to transform them into a different (output) space where it is easier to separate the classes. A visual example of this was provided in figure 1.3.

What is the geometrical nature of the separator? In a very simple situation, such as the one depicted in figure 1.2, the separator is a line in 2D space. In real-life situations, the separator is often a line or a plane in a high-dimensional space. In more complicated situations, the separator is a curved surface, as depicted in figure 1.4.

In this section, we will study the mathematics and geometry behind two types of separators, lines, and planes in high-dimensional spaces, aka hyperlines and hyperplanes.

2.8.1 Multidimensional line equation

In high school geometry, we learned y = mx + c as the equation of a line. But this does not lend itself readily to higher dimensions. Here we will study a better representation of a straight line that works equally well for any finite-dimensional space.

As shown in figure 2.8, a line joining vectors ![]() and

and ![]() can be viewed as the set of points we will encounter if we

can be viewed as the set of points we will encounter if we

-

Start at point

-

Travel along the direction

−

−

Figure 2.8 Any point ![]() on the line joining two vectors

on the line joining two vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() =

= ![]() + α(

+ α(![]() −

−![]() ).

).

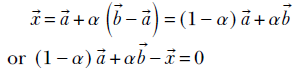

Different points on the line are obtained by traveling different distances. Denoting this arbitrary distance by α, the equation of the line joining vectors ![]() and

and ![]() can be expressed as

can be expressed as

Equation 2.12

Equation 2.12 says that any point on the line joining ![]() and

and ![]() can be obtained as a weighted combination of

can be obtained as a weighted combination of ![]() and

and ![]() , the weights being α and 1 − α. By varying α, we obtain different points on the line. Also, different ranges of α values yield different segments on the line. As shown in figure 2.8, values of α between 0 and 1 yield points between

, the weights being α and 1 − α. By varying α, we obtain different points on the line. Also, different ranges of α values yield different segments on the line. As shown in figure 2.8, values of α between 0 and 1 yield points between ![]() and

and ![]() . Negative values of α yield points to the left of

. Negative values of α yield points to the left of ![]() . Values of α greater than 1 yield points to the right of

. Values of α greater than 1 yield points to the right of ![]() . This equation for a line works for any dimensions, not just two.

. This equation for a line works for any dimensions, not just two.

2.8.2 Multidimensional planes and their role in machine learning

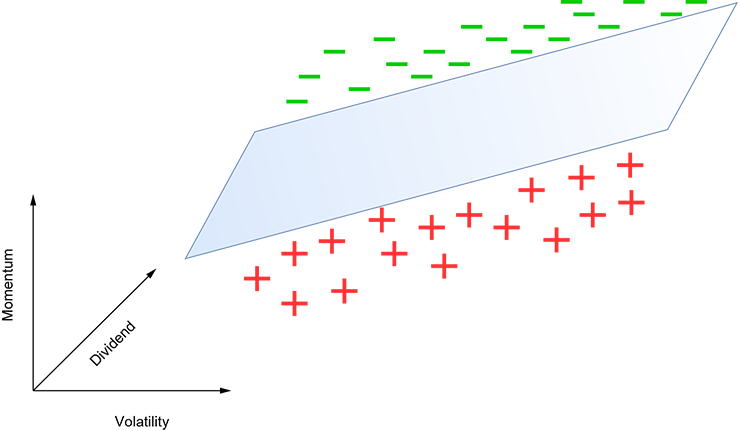

In section 1.5, we encountered classifiers. Let’s take another look at them. Suppose we want to create a classifier that helps us make buy or no-buy decisions on stocks based on only three input variables: 1) momentum, or the rate at which the stock price is changing positive momentum means the stock price is increasing and vice versa); 2) the dividend paid last quarter; and (3) volatility, or how much the price has fluctuated in the last quarter. Let’s plot all training points in the feature space with coordinate axes corresponding to the variables momentum, dividend, volatility. Figure 2.9 shows that the classes can be separated by a plane in the three-dimensional feature space.

Figure 2.9 A toy machine learning classifier for stock buy vs. no-buy decision-making. A plus (+) indicates no-buy, and a dash (-) indicates buy. The decision is made based on three input variables: momentum, dividend, and volatility.

Geometrically speaking, our model simply corresponds to this plane. Input points above the plane indicate buy decisions (dashes [-]), and input points indicate no-buy decisions (pluses [+]). In general, you want to buy high-positive-momentum stocks, so points at the higher end of the momentum axis are likelier to be buy. However, this is not the only indicator. For more volatile stocks, we demand higher momentum to switch from no-buy to buy. This is why the plane slopes upward (higher momentum) as we move rightward (higher volatility). Also, we demand less momentum for stocks with higher dividends. This is why the plane slopes downward (lower momentum) as we go toward higher dividends.

Real problems have more dimensions, of course (since many more inputs are involved in the decision), and the separator becomes a hyperplane. Also, in real-life problems, the points are often too intertwined in the input space for any separator to work. We first have to apply a transformation that maps the point to an output space where it is easier to separate. Given their significance as class separators in machine learning, we will study hyperplanes in this section.

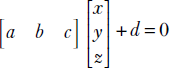

In high school 3D geometry, we learned ax + by + cz + d = 0 as the equation of a plane. Now we will study a version of it that works in higher dimensions.

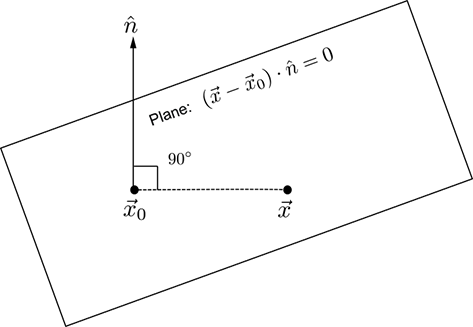

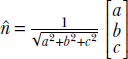

Geometrically speaking, given a plane (in any dimension), we can find a direction called the normal direction, denoted n̂, such that

-

If we take any pair of points on the plane, say

0 and

0 and  , …

, … -

The line joining

and

and  0—i.e., the vector

0—i.e., the vector  −

−  0—is orthogonal to n̂.

0—is orthogonal to n̂.

Thus, if we know a fixed point on the plane, say ![]() 0, then all points on the plane will satisfy

0, then all points on the plane will satisfy

n̂ · (![]() −

− ![]() 0) = 0

0) = 0

or

n̂T(![]() −

− ![]() 0) = 0

0) = 0

Thus we can express the equation of a plane as

n̂T![]() − n̂T

− n̂T![]() 0 = 0

0 = 0

Equation 2.13

Equation 2.13 is depicted pictorially in figure 2.10.

Figure 2.10 The normal to the plane is the same at all points on the plane. This is the fundamental property of a plane. n̂ depicts that normal direction. Let ![]() 0 be a point on the plane. All other points on the plane, depicted as

0 be a point on the plane. All other points on the plane, depicted as ![]() , will satisfy the equation (

, will satisfy the equation (![]() −

−![]() 0) ⋅ n̂ = 0. This physically says that the line joining a known point

0) ⋅ n̂ = 0. This physically says that the line joining a known point ![]() 0 on the plane and any other arbitrary point

0 on the plane and any other arbitrary point ![]() on the plane is at right angles to the normal n̂. This formulation works for any dimension.

on the plane is at right angles to the normal n̂. This formulation works for any dimension.

In section 1.3, equation 1.3, we encountered the simplest machine learning model: a weighted sum of inputs along with a bias. Denoting the inputs as ![]() , the weights as

, the weights as ![]() , and the bias as b, this model was depicted as

, and the bias as b, this model was depicted as

![]() T

T![]() + b = 0

+ b = 0

Equation 2.14

Comparing equations 2.13 and 2.14 , we get the geometric significance: the simple model of equation 1.3 is nothing but a planar separator. Its weight vector ![]() corresponds to the plane’s orientation (normal). The bias b corresponds to the plane’s location (a fixed point on the plane). During training, we are learning the weights and biases—this is essentially learning the orientation and position of the optimal plane that will separate the training inputs. To be consistent with the machine learning paradigm, henceforth we will write the equation of a hyperplane as equation 2.14 for some constant

corresponds to the plane’s orientation (normal). The bias b corresponds to the plane’s location (a fixed point on the plane). During training, we are learning the weights and biases—this is essentially learning the orientation and position of the optimal plane that will separate the training inputs. To be consistent with the machine learning paradigm, henceforth we will write the equation of a hyperplane as equation 2.14 for some constant ![]() and b.

and b.

Note that ![]() need not be a unit-length vector. Since the right-hand side is zero, if necessary, we can divide both sides by ||

need not be a unit-length vector. Since the right-hand side is zero, if necessary, we can divide both sides by ||![]() || to convert to a form like equation 2.13.

|| to convert to a form like equation 2.13.

The sign of the expression ![]() T

T![]() + b has special significance. All points

+ b has special significance. All points ![]() for which

for which ![]() T

T![]() + b < 0 lie on the same side of the hyperplane. All points

+ b < 0 lie on the same side of the hyperplane. All points ![]() for which

for which ![]() T

T![]() + b > 0 lie on the other side of the hyperplane. And of course, all points

+ b > 0 lie on the other side of the hyperplane. And of course, all points ![]() for which

for which ![]() T

T![]() + b = 0 lie on the hyperplane.

+ b = 0 lie on the hyperplane.

It should be noted that the 3D equation ax + by + cz + d = 0 is a special case of equation 2.14 because ax + by + cz + d = 0 can be rewritten as

which is same as ![]() T

T![]() + b = 0 with

+ b = 0 with  and

and  . Incidentally, this tells us that in 3D, the normal to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 is

. Incidentally, this tells us that in 3D, the normal to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 is  .

.

2.9 Linear combinations, vector spans, basis vectors, and collinearity preservation

by now, it should be clear that machine learning and data science are all about points in high-dimensional spaces. Consequently, it behooves us to have a decent understanding of these spaces. For instance, given a space, we may need to ask, “Would it be possible to express all points in the space in terms of a set of a few vectors? What is the smallest set of vectors we really need for that purpose?” This section is devoted to the study of these questions.

2.9.1 Linear dependence

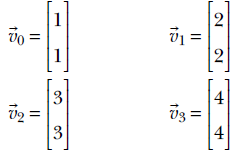

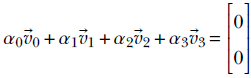

Consider the vectors (points) shown in figure 2.11. The corresponding vectors in 2D are

We can find four scalars α0 = 2, α1 = 2, α2 = 2, and α3 = −3 such that

If we can find such scalars, not all zero, we say the vectors ![]() 0,

0, ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2, and

2, and ![]() 3 are linearly dependent. The geometric picture to keep in mind is that points corresponding to linearly dependent vectors lie on a single straight line in the space containing them.

3 are linearly dependent. The geometric picture to keep in mind is that points corresponding to linearly dependent vectors lie on a single straight line in the space containing them.

Figure 2.11 Linearly dependent points in a 2D plane

Collinearity implies linear dependence

Proof: Let ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() be three collinear vectors. From equation 2.12, there exists some α ∈ ℝ such that

be three collinear vectors. From equation 2.12, there exists some α ∈ ℝ such that

![]() = (1−α)

= (1−α)![]() + α

+ α![]()

This equation can be rewritten as

α1![]() + α2

+ α2![]() + α3

+ α3![]() = 0

= 0

where α1 = (1−α), α2 = α and α3 = −1. Thus we have proven that three collinear vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() must also be linearly dependent.

must also be linearly dependent.

Linear combination

Given a set of vectors ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2, ….

2, …. ![]() n and a set of scalar weights α1, α2, …αn, the weighted sum α1

n and a set of scalar weights α1, α2, …αn, the weighted sum α1![]() 1 + α2

1 + α2![]() 2 + + … αn

2 + + … αn![]() n is called a linear combination.

n is called a linear combination.

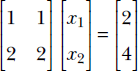

Generic multidimensional definition of linear dependence

A set of vectors ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2, ….

2, …. ![]() n are linearly dependent if there exists a set of weights α1, α2, …αn, not all zeros, such that α1

n are linearly dependent if there exists a set of weights α1, α2, …αn, not all zeros, such that α1![]() 1 + α2

1 + α2![]() 2 + + … αn

2 + + … αn![]() n = 0. For example, the row vectors [1 1] and [2 2] are linearly dependent, since –2[1 1] + [2 2] = 0.

n = 0. For example, the row vectors [1 1] and [2 2] are linearly dependent, since –2[1 1] + [2 2] = 0.

2.9.2 Span of a set of vectors

Given a set of vectors ![]() 1,

1, ![]() 2, ….

2, …. ![]() n, their span is defined as the set of all vectors that are linear combinations of the original set . This includes the original vectors.

n, their span is defined as the set of all vectors that are linear combinations of the original set . This includes the original vectors.

For example, consider the two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() . The span of these two vectors is the entire plane containing the two vectors. Any vector, for instance, the vector

. The span of these two vectors is the entire plane containing the two vectors. Any vector, for instance, the vector ![]() can be expressed as a weighted sum 18

can be expressed as a weighted sum 18![]() x⊥ + 97

x⊥ + 97![]() y⊥.

y⊥.

You can probably recognize that ![]() and

and ![]() are the familiar Cartesian coordinate axes (X-axis and Y-axis, respectively) in the 2D plane.

are the familiar Cartesian coordinate axes (X-axis and Y-axis, respectively) in the 2D plane.

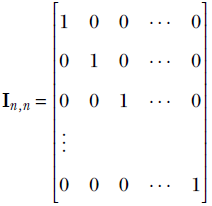

2.9.3 Vector spaces, basis vectors, and closure

We have been talking informally about vector spaces. It is time to define them more precisely.

Vector spaces

A set of vectors (points) in n dimensions form a vector space if and only if the operations of addition and scalar multiplication are defined on the set. In particular, this implies that it is possible to take linear combinations of members of a vector space.

Basis vectors

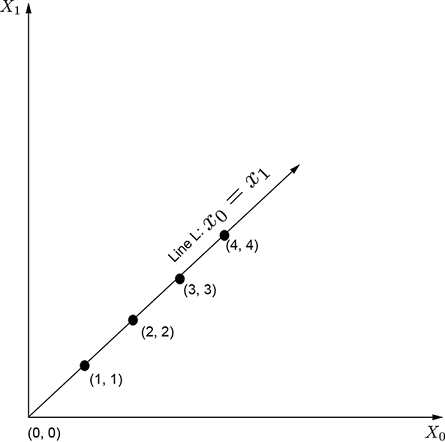

Given a vector space, a set of vectors that span the space is called a basis for the space. For instance, for the space ℝ2, the two vectors ![]() and

and ![]() are basis vectors. This essentially means any vector in ℝ2 can be expressed as a linear combination of these two. The notion can be extended to higher dimensions. For ℝn, the vectors

are basis vectors. This essentially means any vector in ℝ2 can be expressed as a linear combination of these two. The notion can be extended to higher dimensions. For ℝn, the vectors  form a basis.

form a basis.

The alert reader has probably guessed by now that the basis vectors are related to coordinate axes. In fact, the basis vectors just described constitute the Cartesian coordinate axes.

So far, we have only seen examples of basis vectors that are mutually orthogonal, such as the dot product of the two basis vectors in ℝ2 shown earlier:  . However, basis vectors do not have to be orthogonal. Any pair of linearly independent vectors forms a basis in ℝ2. Basis vectors, then, are by no means unique. That said, orthogonal vectors are most convenient, as we shall see later.

. However, basis vectors do not have to be orthogonal. Any pair of linearly independent vectors forms a basis in ℝ2. Basis vectors, then, are by no means unique. That said, orthogonal vectors are most convenient, as we shall see later.

Minimal and complete basis

Exactly n vectors are needed to span a space with dimensionality n. This means the basis set for a space will have at least as many elements as the dimensionality of the space. That many basis vectors are also sufficient to form a basis. For instance, exactly n vectors are needed to form a basis in (that is, span) ℝn.

A related fact is that in ℝn, any set of m vectors with m > n will be linearly dependent. In other words, the largest size of a set of linearly independent vectors in an n-dimensional space is n.

Closure

A set of vectors is said to be closed under linear combination if and only if the linear combination of any pair of vectors in the set also belongs to the same set. Consider the set of points ℝ2. Recall that this is the set of vectors with two real elements. Take any pair of vectors ![]() and

and ![]() in ℝ2: for instance,

in ℝ2: for instance, ![]() and

and ![]() . Any linear combination of these two vectors will also comprise two real numbers—that is, will belong to ℝ2. We say ℝ2 is a vector space since it is closed under linear combination.

. Any linear combination of these two vectors will also comprise two real numbers—that is, will belong to ℝ2. We say ℝ2 is a vector space since it is closed under linear combination.

Consider the space ℝ2. Geometrically speaking, this represents a two dimensional plane. Let’s take two points on this plane, ![]() and

and ![]() . Linear combinations of

. Linear combinations of ![]() ,

, ![]() geometrically correspond to points on the line joining them. We know that if two points lie on a plane, the entire line will also lie on the plane. Thus, in two dimensions, a plane is closed under linear combinations. This is the geometrical intuition behind the notion of closure on vector spaces. It can be extended to arbitrary dimensions.

geometrically correspond to points on the line joining them. We know that if two points lie on a plane, the entire line will also lie on the plane. Thus, in two dimensions, a plane is closed under linear combinations. This is the geometrical intuition behind the notion of closure on vector spaces. It can be extended to arbitrary dimensions.

On the other hand, the set of points on the surface of a sphere is not closed under linear combination because the line joining an arbitrary pair of points on this set will not wholly lie on the surface of that sphere.

2.10 Linear transforms: Geometric and algebraic interpretations

Inputs to a machine learning or data science system are typically feature vectors (introduced in section 2.1) in high-dimensional spaces. Each individual dimension of the feature vector corresponds to a particular property of the input. Thus, the feature vector is a descriptor for the particular input instance. It can be viewed as a point in the feature space. We usually transform the points to a friendlier space where it is easier to perform the analysis we are trying to do. For instance, if we are building a classifier, we try to transform the input into a space where the points belonging to different classes are more segregated (see section 1.3 in general and figure 1.3 in particular for simple examples). Sometimes we transform to simplify the data, eliminating axes along which there is scant variation in the data. Given their significance in machine learning, in this section we will study the basics of transforms.

Informally, a transform is an operation that maps a set of points vectors) to another. Given a set S of n × 1 vectors, any m × n matrix T can be viewed as a transform. If ![]() belongs to the set S, multiplication with the matrix T will map (transform)

belongs to the set S, multiplication with the matrix T will map (transform) ![]() to a vector T

to a vector T![]() . We will later see that matrix multiplication is a subclass of transforms that preserve collinearity—points that lie on a straight line before the transformation will continue to lie on a (possibly different) straight line post the transformation. For instance, consider the matrix

. We will later see that matrix multiplication is a subclass of transforms that preserve collinearity—points that lie on a straight line before the transformation will continue to lie on a (possibly different) straight line post the transformation. For instance, consider the matrix

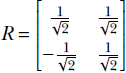

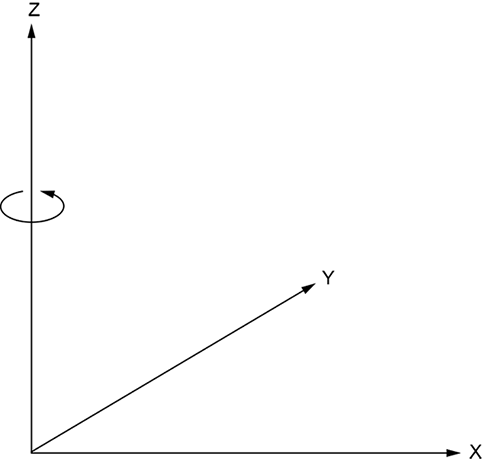

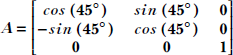

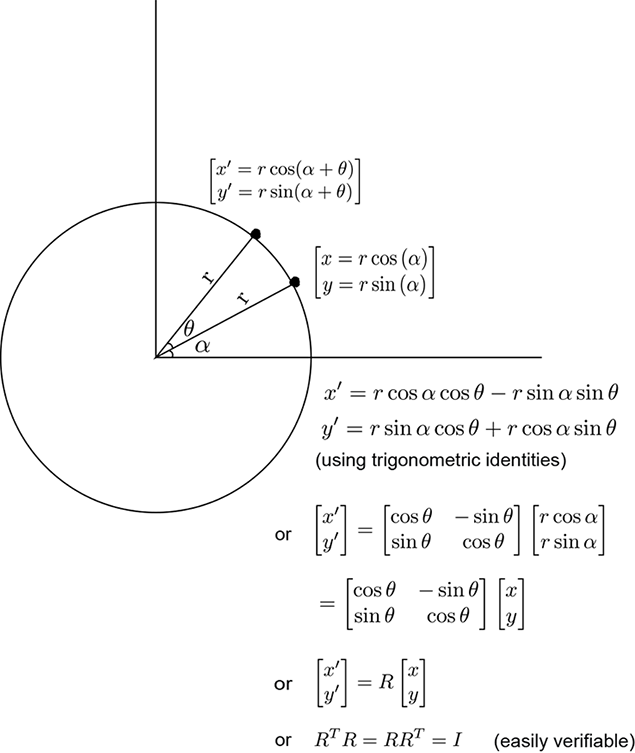

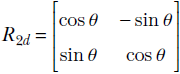

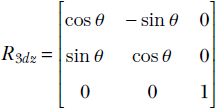

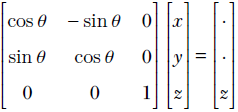

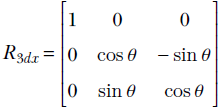

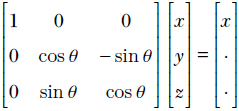

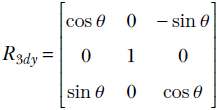

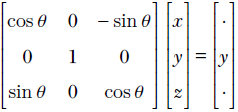

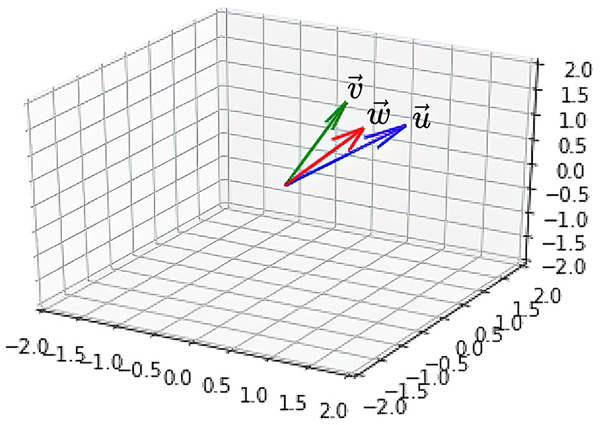

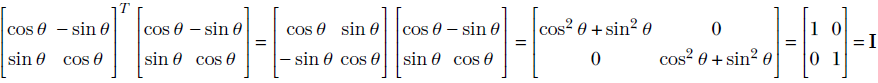

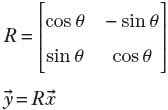

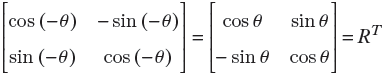

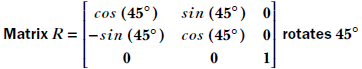

In section 2.14, we will see that this is a special kind of matrix called a rotation matrix; for now, simply consider it an example of a matrix. R is a transformation operator that maps a point in a 2D plane to another point in the same plane. In mathematical notation, R : ℝ2 → ℝ2. In fact, as depicted in figure 2.14, this transformation (multiplication by matrix R) rotates the position vector of a point in the 2D plane by an angle of 45°.

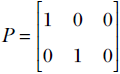

The output and input points may belong to different spaces in such transforms. For instance, consider the matrix

It is not hard to see that this matrix projects 3D points to the 2D X-Y plane:

Hence, this transformation (multiplication by matrix P) projects points from three to two dimensions. In mathematical parlance, P : ℝ3 → ℝ2.

The transforms R and P share a common property: they preserve collinearity. This means a set of vectors (points) ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , ⋯ that originally lay on a straight line remain so after the transformation.

, ⋯ that originally lay on a straight line remain so after the transformation.

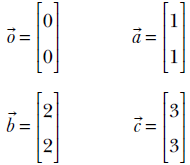

Let’s check this out for the rotation transformation in the example from section 2.9. There we saw four vectors:

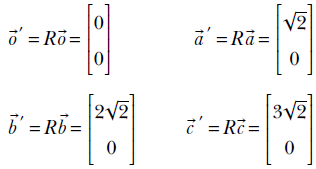

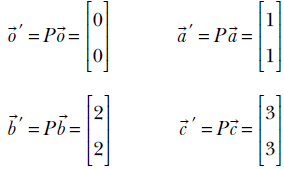

These vectors all lie on a straight L : x = y. The rotation transformed versions of these vectors are

It is trivial to see that the transformed vectors also lie on a (different) straight line. In fact, ![]() ′,

′, ![]() ′,

′, ![]() ′,

′, ![]() ′ lie on the Y-axis, which is the 45° rotated version of the original line y = x.

′ lie on the Y-axis, which is the 45° rotated version of the original line y = x.

It is trivial to see that the transformed vectors also lie on a (different) straight line. In fact, ![]() ′,

′, ![]() ′,

′, ![]() ′,

′, ![]() ′ lie on the Y-axis, which is the 45° rotated version of the original line y = x.

′ lie on the Y-axis, which is the 45° rotated version of the original line y = x.

The projection transform represented by matrix P also preserves collinearity. Consider four collinear vectors in 3D:

The corresponding transformed vectors

also lie on a straight line in 2D.

The class of transforms that preserves collinearity are known as linear transforms. They can always be represented as a matrix multiplication. Conversely, all matrix multiplications represent a linear transformation. A more formal definition is provided later.

2.10.1 Generic multidimensional definition of linear transforms

A function ϕ is a linear transform if and only if it satisfies

ϕ(α![]() + β

+ β![]() ) = αϕ(

) = αϕ(![]() ) + βϕ(

) + βϕ(![]() ) ∀ α, β ∈ ℝ

) ∀ α, β ∈ ℝ

Equation 2.15

In other words, a transform is linear if and only if the transform of the linear combination of two vectors is the same as the linear combination (with the same weights) of the transforms of individual vectors. (This can be remembered as: Linear transform means transforms of linear combinations are same as linear combinations of transforms.) Multiplication with a rotation or projection matrix (shown earlier) is a linear transform.

2.10.2 All matrix-vector multiplications are linear transforms

Let’s verify that matrix multiplication satisfies the definition of linear mapping (equation 2.15). Let ![]() ,

, ![]() ∈ ℝn be two arbitrary n-dimensional vectors and Am, n be an arbitrary matrix with n columns. Then following the standard rules of matrix-vector multiplication,

∈ ℝn be two arbitrary n-dimensional vectors and Am, n be an arbitrary matrix with n columns. Then following the standard rules of matrix-vector multiplication,

A(α![]() + β

+ β![]() ) = α(A

) = α(A![]() ) + β(A

) + β(A![]() )

)

which mimics equation 2.15 with ϕ replaced with matrix A. Thus we have proven that all matrix multiplications are linear transforms. The reverse is not true. In particular, linear transforms that operate on infinite-dimensional vectors are not matrices. But all linear transforms that operate on finite-dimensional vectors can be expressed as matrices. (The proof is a bit more complicated and will be skipped.)

Thus, in finite dimensions, multiplication with a matrix and linear transformation are one and the same thing. In section 2.3, we saw the array view of matrices. The corresponding geometric view, that all matrices represent linear transformation, was presented in this section.

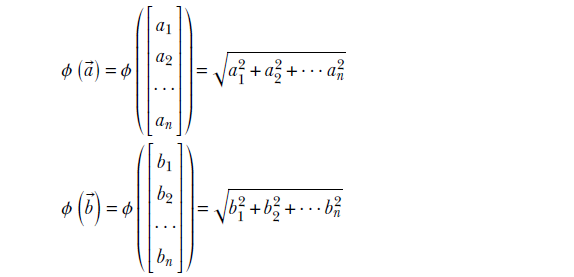

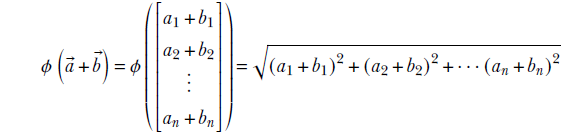

Let’s finish this section by studying an example of a transform that is not linear. Consider the function

ϕ(![]() ) = ||

) = ||![]() ||

||

for ![]() ∈ ℝn. This function ϕ maps n-dimensional vectors to a scalar that is the length of the vector, ϕ : ℝn → ℝ. We will examine if it satisfies equation 2.15 with α1 = α2 = 1. For two specific vectors

∈ ℝn. This function ϕ maps n-dimensional vectors to a scalar that is the length of the vector, ϕ : ℝn → ℝ. We will examine if it satisfies equation 2.15 with α1 = α2 = 1. For two specific vectors ![]() ,

, ![]() ∈ ℝn,

∈ ℝn,

Now

![]()

and

Clearly, these two are not equal; hence, we have violated equation 2.15: ϕ is a nonlinear mapping.

2.11 Multidimensional arrays, multilinear transforms, and tensors

We often hear the term tensor in connection with machine learning. Google’s famous machine learning platform is named TensorFlow. In this section, we will introduce you to the concept of a tensor.

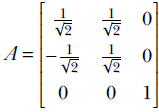

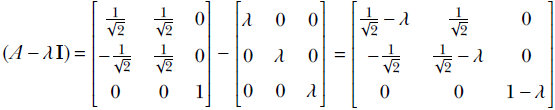

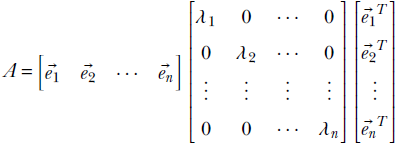

2.11.1 Array view: Multidimensional arrays of numbers